All reasonable steps: a reminder to employers

In 2020, the spotlight will remain on sexual harassment and the need to eliminate it from the workplace. Employers play a vital role in eradicating sexual harassment at work.

A recent Full Federal Court of Australia decision demonstrates the extent of an employer’s role to prevent sexual harassment at work. The Full Court examined the defence of all reasonable steps, concluding that an employer’s responsibility extends beyond the simple existence of policy and the mere provision of training.

Von Schoeler v Allen Taylor and Company Ltd Trading as Boral Timber (No 2) [2020] FCAFC 13

On 20 February 2020 the Full Federal Court allowed an appeal by a worker against a finding of the primary judge that her employer was not liable for the sexual harassment she experienced at work.

The appeal was successful, in part, due to the six-year delay by the judge in delivering his decision rendering the decision “unsafe”.

Critically, while finding the employee was sexually harassed, the primary judge exonerated the employer saying:

“... I decline to find that the [employer] is vicariously liable for the sexual harassment perpetrated by the [perpetrator]. I find that, by developing the policy and conducting training sessions, the [employer] took all reasonable steps to prevent that act occurring.”

The employer had developed a 'Working With Respect' policy that included "substantial" notes on sexual harassment and the employer had conducted training sessions, which the perpetrator attended in the days before the sexual harassment occurred.

Not good enough

Discrimination legislation provides that an employer is vicariously liable for the conduct of its employees unless it establishes it “took all reasonable steps to prevent the employee ... from doing” the prohibited act.

“The word “all” is significant. It is not enough for the employer to demonstrate that it took some of the reasonable steps available to prevent the employee from doing the unlawful act”, the Full Court said.

In providing valuable guidance the Full Court said:

61. However, it is unnecessary for the employer to take all steps necessary to prevent the employee ... from doing the relevant act. What must be taken is all steps that are reasonable to take. What steps are reasonable will depend upon the whole of the circumstances, including the size of the organisation, the nature of its workforce, the conditions under which the work is carried out and any history of unlawful discrimination or sexual harassment.

62. The reasonable steps taken must be “to prevent” the employee ... from engaging in the unlawful discrimination or sexual harassment. The focus is upon preventative steps taken before any relevant act occurs. However, in some circumstances, the way a complaint is dealt with after the act may have relevance to the question of whether all reasonable preventative steps were taken. For example, a failure by an employer to comply with policies for investigating and dealing with complaints may be reflective of a workplace culture that tolerates unlawful discrimination or sexual harassment.

63. Further, the focus must be on what steps would or might prevent an employee from doing the relevant unlawful act. A criticism that may be levelled at some of the cases decided by anti-discrimination bodies in this area is that they tend to focus upon perceived deficiencies in policies and training without adequate consideration of whether those deficiencies could have made any difference to the doing of the relevant act.

In this case, and to avoid vicarious liability, the employer put into evidence its policy and training slides as the evidence of the reasonable steps taken by it.

The Full Court was critical of this evidence saying, “there is a paucity of evidence as to the content of the information and training provided”. The evidence tendered did not explain the policy or the content of the training. In fact, the slides were of a refresher training course eight months after the incident! The Full Court’s criticisms also included observations about a lack of evidence as to:

-

the meaning and understanding of employees about the expression “zero tolerance“ for sexual harassment;

-

whether employees were told the employer would take disciplinary action in respect of sexual harassment; and

-

whether the employees, in addition to the training, had been given and explained the policy prohibiting sexual harassment.

The Full Court found the perpetrator was neither made aware of the zero-tolerance policy nor that disciplinary action would be taken with respect to such conduct. Further, the effectiveness of any training was also brought into question where the sexual harassment occurred four days after the training.

The Full Court has said the all reasonable steps defence requires substantial evidence.

What must employers do

Policies are important. “The significance of effective policies and training includes that they deter unlawful discrimination and sexual harassment”, the Full Court commented. But policies are only the start of all reasonable steps. Relying on the mere existence of a policy will not be good enough: Menere v Poolrite Equipment Pty Ltd [2012] QCAT 505.

Training is the next obvious step. Employers need an education program: STU v JKL (Qld) Pty Ltd [2017] QCAT 505. As identified by the Full Court, a relevant factor in determining whether reasonable steps were taken is the conformity of training and policies with the Australian Human Rights Commission guidelines on Effectively Preventing and Responding to Sexual Harassment. Importantly, policy and training are just the beginning.

Past cases have given us good indicators on what are reasonable steps. These cases and their lessons include:

-

the mere presence of management in the workplace is not itself a disincentive to misconduct: Gilroy v Angelo [2000] FCA 1775, but appropriate supervision (and or auditing) is an important step to ensure no inappropriate behaviour and culture;

-

the policy should also tell employee of personal consequences of their conduct, including criminal: Richardson v Oracle Corporation Australia Pty Limited [2013] FCA 102, as a means to deter inappropriate behaviour;

-

education and training should be broader in scope and encompass training employees on how to manage an uncomfortable situation: Menere v Poolrite Equipment Pty Ltd [2012] QCAT 252, thereby giving them the tools to protect their safety and to speak up;

-

‘tool box talk’ sessions, reminders and distribution of information leaflets are “all the right things” to do: Murugesu v Australian Postal Corporation [2015] FCCA 2852, Howard v Geradin Pty Ltd [2004] VCAT 1518, as merely having annual training may not impart the seriousness of the topic. The Full Court highlighted that policies should be “periodically reinforced”;

-

any policy needs to be supported by an effective complaint management system, with a real and reasonable opportunity for workers to raise complaints: Gilroy v Angelov [2000] FCA 1775;

-

employers need to actively engage with any complaint received and not ignore or treat the complaint with skepticism: Murugesu v Australian Postal Corporation [2015] FCCA 2852; Webb v State of Queensland [2006] QADT 8. How employer’s respond to complaints impacts on the confidence of the workforce to report inappropriate behaviour;

-

employers need to act on informal reports of offending behaviour (including what is anonymous or confidential): Webb v State of Queensland [2006] QADT 8, as this demonstrates it takes the eradication of sexual harassment seriously; and

-

employers must take risk management action immediately once aware of complaint: Smyth v Northern Territory Treasury [2016] NTADComm 1, as ensuring worker safety is paramount.

Steps to take after an investigation (other than discipline)

As is apparent, how employers respond to a complaint is important in showing all reasonable steps have been taken. Equally, the management and response to an investigation and its outcomes are important.

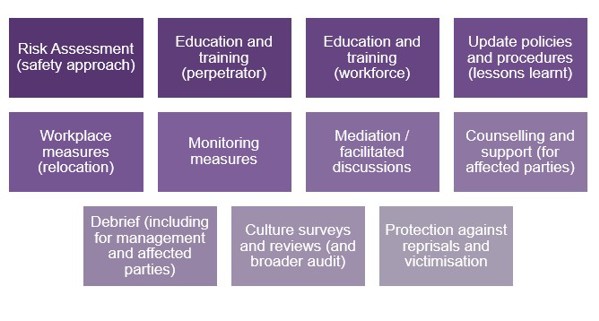

Steps that need to be taken, include:

Good HR practice would be to ‘check-in’ with the complainant (and or perpetrator, if not dismissed) and the business unit, routinely in the 12 months after the investigation to ensure normality has returned and lessons learnt have been implemented.

Tips

At a more holistic level, our five hot tips on managing a complaint of sexual harassment are:

-

Always act to ensure workplace safety: this must be your guiding principle and purpose (but ensure no victimisation of the complainant in implementing any interim risk management measures). This includes having an effective policy, complaint management system and education and training.

-

Stand up for workplace culture: do not be afraid to take appropriate and fair but decisive action to demonstrate you do not tolerate inappropriate behaviours.

-

Ensure you have taken risk management measures throughout the entire process and afterwards: consistent with your overriding purpose you must continue as you began.

-

Stay in touch with all parties and the business at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after the investigation is completed: what’s the thermometer?

-

Undertake a review: the business should assess if it has been successful in dealing with and closing off the matter.

Author: James Mattson